“It’s everybody’s fight.”

Viola Gregg Liuzzo

Viola Gregg Liuzzo is the only white woman to be murdered during the Civil Rights movement; her death sparked the passage of the Voting Rights Act. Her name is engraved on the National Civil Rights Memorial in Birmingham, Alabama along with those of forty others, including the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., Medgar Evers, the four little girls who perished in the 16th Street Baptist Church bombing, and “Mississippi Burning” victims Chaney, Schwerner, and Goodman. Our goal is to memorialize Mrs. Liuzzo in her birthplace and early childhood home of California, Pa.

Committee members

Lisa Buday

Rosemary Capanna

Frank Kurtik

Christopher Sepesy

Bio and Background

Click on photos to enlarge. All photos courtesy of the Liuzzo family, except where noted.

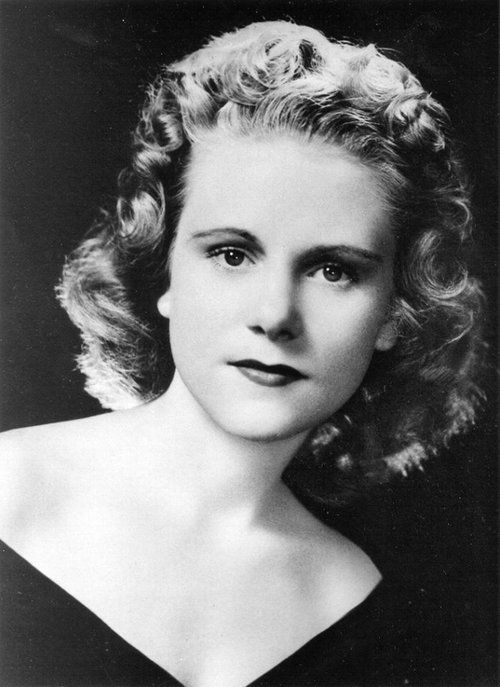

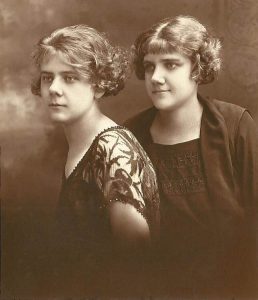

Eva Wilson Gregg with her daughter, Viola Gregg. This photo was taken in Phillipsburg, a small community located within East Pike Run Township.

Viola Fauver Gregg was born in her maternal grandmother’s home on Park Street in East Pike Run Township (California), Pa. on April 11, 1925. Her father, Heber Gregg, was a coal miner. Her mother, Eva Estelle Wilson, graduated from East Pike Run Township High School and Southwestern PA Normal School (now California University of Pennsylvania) and taught throughout the area.

Viola and her parents resided with Eva’s mother, Sarah Fauver Wilson, on Park Street. The area was, at the time, ethnically segregated from California, reserved for immigrants (only those of English descent could live in California proper). Heber eventually lost a hand in a mine explosion and the family traveled south, to Georgia, when Viola was six. In 1935 they had another daughter, Rose Mary, and settled in Detroit, where Eva worked in bomb assembly and later at the Ford Motor Company plant.

Information about Viola’s birth in East Pike Run was included in the FBI files that were obtained by her family through a Freedom of Information Act request.

After two failed marriages, Viola married Anthony Liuzzo in 1950 (they had three children together and she had two from a previous marriage). Anthony was a Teamsters official who counted Jimmy Hoffa among his friends.

Having spent part of her childhood in the South, Viola experienced racial prejudice and segregation firsthand. She joined the Detroit chapter of the NAACP. She also became a member of the Unitarian Universalist Church. By all accounts she was an intelligent, strong, empathetic woman who wanted to make the world a better place.

As racial tensions swelled throughout the south in the spring of 1965, the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) held a protest march in Selma, Alabama on March 7 to demand voting rights for all. The infamously brutal confrontation between six hundred protestors and Alabama state troopers at the Edmund Pettus Bridge became known as “Bloody Sunday.” By this time Viola was thirty-nine-years old and enrolled at Wayne State University, studying sociology. She participated with other students in protests against segregation and the escalating violence.

Viola’s daughter, Mary Liuzzo Lilleboe, recounted the events that led up to her mother’s participation: “My mother and father were watching television in March, 1965 when a news alert broke into the programming and showed the Bloody Sunday brutality on the Edmond Pettus Bridge. Later, Dr. King was on TV making a plea: ‘The people of Selma will struggle on for the soul of the nation, but it is fitting that all Americans help to bear the burden. I call therefore on clergy of all faiths, representatives of every part of the country, to join me in Selma for a march to Montgomery…’

Viola Liuzzo was murdered by KKK members while she was shuttling protesters back to Selma after the Selma to Montgomery Voting Rights March.

“I know my mother made up her mind at that moment to go to Selma. She didn’t want Dad to try to stop her (not that he could have) so she called him and said she was going. Dad tried to tell her it wasn’t her fight. Her response was, ‘It’s everybody’s fight.’ She drove the 850+ miles to Selma alone.”

The march that the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. and other leaders planned was to begin on Sunday, March 21. More than 3000 activists of varying racial, religious, and economic backgrounds soon arrived.

Viola volunteered to help with the event, so the SCLC put her to work greeting newcomers at the Brown Chapel reception desk in Selma. One of the people she met was nineteen-year-old Leroy Moton. Viola marched and assisted at a first aid station as well (she had earned a medical technician certificate from the Carnegie Institute in Detroit).

It took the protestors five days to reach Montgomery and by then their numbers had grown to 25,000. Dr. King spoke to the crowd from the steps of the state capitol, famously encouraging them that their efforts were worthwhile because, “…the arc of the moral universe is long, but it bends toward justice.”

As the protest wound down Viola insisted that she would continue to volunteer by transporting demonstrators back to Selma in her Oldsmobile. After dropping off some passengers, she and Leroy Moton headed back to Montgomery. Members of the Ku Klux Klan, who were infuriated by the march and the influx of “outside agitators,” took note of the Michigan license plate and “race mixing” – a white woman was alone in a car with an African American man, a serious transgression in the Jim Crow south. The four Klansmen pursued Liuzzo, who attempted to outrun them. They tried to run her off the road, eventually catching up with her car on a lonely stretch of U.S. Route 80 in Lowndesboro, Alabama. Pulling beside her, they fired two rounds into her head, killing her instantly. Viola’s car careened into a ditch, traveling a short distance before it came to a stop against a fence. Moton wasn’t hit but he was covered in Viola’s blood. He pretended to be dead when the Klansmen backtracked to check on their victims. When they left, Moton ran for help and was picked up by another driver who was also shuttling protesters.

“I was at my grandparents’ home in Georgia when Mom went to Selma,” recalled Mrs. Lilleboe. “She was going to pick me up on the way home. I remember Grandma telling me right after she received the phone call, ‘Your Mother has been shot and killed in Selma, Alabama.’ That is what I remember but I don’t know what else, if anything, Grandma said. And then everything became unreal. I was moving and talking but I wasn’t feeling anything. We were leaving for Detroit the next morning and I know I fell asleep because I remember waking up and trying to remember if I had been dreaming. I don’t remember getting into the car or if we talked. Then something happened that startled me. Grandma, Grandpa, and I walked into a restaurant and I heard Grandma cry out, ‘Oh, my baby.’ She was looking at the front page of the paper that was displayed in the coin operated newsstand; a picture of my beautiful Mom looked back at me. My breath caught and it was like waking up. Through the noise inside of me I remember one thought, I don’t know why it struck me so, but I realized she wasn’t just my mother – she was my Grandma’s baby, my aunt’s sister, my Dad’s wife. I was overcome with the magnitude of a person’s life. So many people touched by the loss, so many more than just me. Little did I know that my Mom’s life would touch thousands of lives, many who would never know her but would love her, thank her, and honor her.”

Viola Liuzzo’s murder rocked much of America and jarred many citizens out of their apathetic complacency – she was a white, middle class mother with five children who was peacefully seeking to help right an injustice. President Lyndon Johnson appeared on television the next day and said that, “Mrs. Liuzzo went to Alabama to serve the struggle for justice. She was murdered by the enemies of justice, who for decades have used the rope and the gun and the tar and feathers to terrorize their neighbors.” He also cited her violent death as he implored Congress to pass the Voting Rights Act, which until then had been viewed as a longshot to receive the support it needed to become law. The tragic events in Alabama helped it garner approval from all quarters, and Johnson signed the bill a few months later.

Viola’s assassins were apprehended in a matter of hours. One of the four, Gary Thomas Rowe, Jr., was an FBI informant. He avoided prosecution by testifying against the other three men. The first trial ended in a mistrial. They were found not guilty of murder in the second trial. However, a federal trial soon followed and the three men were found guilty of violating Liuzzo’s civil rights. They served 10 years in prison. Later it was revealed that Rowe, who avoided jail time and died after thirty years in the witness protection program, had beaten Freedom Riders and most likely had participated in the Birmingham Church bombing in 1963, where four little girls were killed. Some believe he may have been the triggerman in Viola’s murder.

The National Civil Rights Martyrs Monument in Birmingham, AL. Photo by Eric Hunt, used under the Creative Commons license. https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.5

At the direction of J. Edgar Hoover, in an effort to protect their informant and avoid any appearance of bungling or complicity in Liuzzo’s death, the FBI immediately began a lurid smear campaign against her. They accused her of mental illness, abandoning her family, being a drug addict, sexual promiscuity with African American men, and marrying a man who was involved with organized crime. In 1978 Liuzzo’s children petitioned her FBI documents via the Freedom of Information Act. Though they proved that none of the accusations were true, the years of insinuation and rumors had done their damage. A Ladies Home Journal survey biasedly asked if Viola was partially to blame for her own murder; 55% of their readers agreed. The Liuzzo children endured racial taunts and a cross was burned on their lawn in Detroit. Anthony Liuzzo began to drink heavily. One of Liuzzo’s sons moved from Detroit and changed his last name to Lee, to avoid being asked if he was related to her. But they also received the support of friends as well as letters of sympathy from across the country. President Johnson called the shocked and grieving family several times the day she died. Martin Luther King, Jr., Rosa Parks, and other African American leaders attended her funeral, and King remained in contact with the family until his death.

History took a while to correct itself but, as time passed and the arc of the moral universe bent toward justice, Viola’s sacrifice and contribution to the Civil Rights movement became more apparent. She is the only white woman to be acknowledged as a Civil Rights martyr. In 1989 her name was one of forty-one inscribed on the National Civil Rights Memorial in Montgomery. In 1991, the women of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference placed a marker in her honor on Route 80 at the place of her death. Additionally, she has been inducted into the Michigan Women’s Hall of Fame. She received a Ford Freedom Award for her humanitarian work as well as The National Race Amity Award, among other distinctions.

The interest in her life and tragic murder escalated this past year as plans to commemorate the 50th anniversary of the Selma to Montgomery March took shape. The Academy Award-winning film, Selma, featured a small but powerful portrayal of Viola by actress Tara Ochs. The filmmakers didn’t identify Ochs’ character as Liuzzo, but a caption at the end of the movie did and noted her murder by Klansmen. As part of a three day event taking place April 10-12 to mark what would have been her 90th birthday, her alma mater, Wayne University in Detroit, is bestowing upon her a posthumous degree – an honorary Doctor of Laws. It is the first distinction of its type ever issued by the school.

California, Pa. has yet to honor Viola Liuzzo in any way.

Originally published in PA Bridges, April 2015. Additional information compiled by Rosemary Capanna for California Area re:Generations. © Copyright 2020 Rosemary Capanna. All rights reserved.